The Jester Race

by Drew Reichard

Though you look, you can’t find episode #1. It appears not to exist in any form on the Web, and in hours of forum-scanning and search engine detective work, it’s never alluded to, not even once.

Episodes 2 through 38 come up on some illicit-looking streaming sites—websites like camper communities, thrown up in monotone simplicity whose implicit purpose appears to be hosting ad-blocker defying porno GIFs. You weigh the risks of lingering, of committing to the triangular play button on the iframe against the possibility of opening your virgin laptop to a virus. You bounce.

The internet is a warfront, and here you are just for idle entertainment on a morning without commitments, but the hype on your favorite forums has intrigued you, and now the hunt is on: an internet-only anime serial of unknown origin. The show is secretive and cultic to its core, harboring a following of diehard otakus whose avatars all express their loyalty to the series. The banishment of episode 1 seems itself part of the draw.

Frustrated by this chronological setback, but still curious, you experimentally begin with easier-to-locate Episode 39: “The Jester’s Dance.”

#

And are introduced to the characters via theme song and montage. In motion and music, the heroic pair seem alive and incapable of disappointing. The female is fascinating and surprisingly modest. Serious eyes—one of them red, the other black—fixate on a bladescape of enemies as you see her intermittently freestyle fighting and rising on a marmoreal pillar with her partner. Her clothing sleeve-wild and extraneous, though it never appears to hamper her. And her weapon of choice seems to you like a sentient fishing rod, snake-flashing of its own accord. Her companion, the male, is stranger still: he leaps and capers in business suit body with a flapping tie depicting a handsome face, but the head above the collar is a closed jack-in-the-box complete with wind-up handle. The theme song reaches fade out, closes on a humorous moment of the male’s clownish dollhead exploding from his jack’s box to plant an unwanted kiss on the heroine’s cheek. The two turn their backs on the audience toward a rising sun in a high place, her hair flailing in the wind, hands on hips, the man’s spring-loaded neck bobbing mischievously, and the overture fades to the title of Episode 39…

#

The Jester’s Dance

She comes up the dirt street of a feudal town with her fishing rod on her shoulder and a pail of worms, whistling. No one passes her on the road, but she can see the rice farmers in their straw hats far afield. They don’t look up as she passes, and she turns onto a deer track that leads downhill to the river to put in her line.

“You won’t catch anything, Roco. It’s too late in the day for fish.”

Startled, Roco spins to find that he’s anticipated her and ruined her peace.

Loon reclining against a tree, holding a book open in front of his tie upon which the picturesque face apparently reads, eyes swiveling. His boxhead is closed; the tie speaks. “I was getting bored in town waiting for you, so I decided to, uh, preemptively, uh…”

Her face begins to brim with storm cloud, red asterisks bleeping on a ballooning forehead.

“You’re angry.”

“You think? My one day of peace without you capering after me and you ruin it by following me and then telling me there are no fish!”

(Watching this display of seemingly transparent character development and uneventful dialogue, you are bemused, maybe skeptical. Roco’s fishing line seems like a metaphor, but of what you’re not certain.)

In the face of Roco’s anger, Loon’s tie turns a capitulate white, waving, the figure on it hiding behind a tree like the real one Loon himself had been lounging against. The book in his hand flutters away like a bird, and he doesn’t notice the line Roco never took out of the water, which has been busy extending eelishly. It snares his foot and, before he knows bank from branch, has him dangling upside down over rapids which had waited patiently to digitally present themselves until they were needed.

Roco’s sleeves lengthen into what could only be battle mode; her clothing seems all stitching and munching suture lines, loose threads medusa-like. The fishing line winds itself around Loon’s legs up to the knees and begins, to his horror, to metronome him back and forth.

Roco picks up the pail with the extending threads of her colorful clothes, and they retract again as if by magic.

“Roco, now let’s talk about this. What have I said about your temper?” Loon, upside down, gulps. “Oh, come on. Put the worms down. This isn’t funny. Roco!”

“Just one worm. You deserve it.”

“No. Put me down.”

“What about the ear? A wet willie worm. Come on out, jack; you can’t hide in that box forever.”

“Can and will.” Seeing her begin to relent, though, Loon switches from terror to a cross-armed pout, still hanging box down. The man on his tie has reoriented himself and is also a picture of impatience, issuing forth extravagant glowers.

Roco reels the line in and drops him in the shallows.

“That was mean.”

“Couldn’t help myself. You still ruined my evening. Here.” She helps him up. “What have I told you about following me?”

“At least you caught something.” But this is from a third voice, and the two characters whirl to face the joker emerging from the woods behind them.

Roco’s line makes a scorpion tail behind her. The figure on Loon’s tie—more cartoon than the cartoon he’s in—manufactures a rocket launcher from a tiny side holster and performs a G. I. stance.

“Easy does it,” the newcomer drawls, putting his hands up near the tuba strapped to his back. He is gable-shouldered and marching-band-booted, wearing a flaring overcoat and checkered face paint. He looks like the tuba he bears.

“Keep your hands away from that instrument.”

But too late. The cartoon world distends into motion lines as all three characters draw weapons and ignite into action. Before your eyes, the episode rears into a different technique. The setting slips into blurriness. Background objects take on a copied-and-pasted look as the angle holds tightly to the three battling figures in the foreground. And now you are introduced to the show’s method of animating fight scenes. The creators have eschewed the usual rapid-fire shortcuts in favor of intricate detail on a narrow focus. Every point of contact has its crystalline concentration. Only the setting recedes, and only then if the characters don’t encounter these lesser objects. When they do—as when Roco runs up the bole of a tree and backflips over a tangible bellow from the tuba—the tree she touches turns resplendent: the knotted bark, the veins in the leaves. The branch Roco snares with her fishing line in the last second before she leaps creaks with a stunning precision of sound. Roco, swinging by the rod, plants the heels of her feet into the Jester’s unwitting back, and you hear the spine snap. You see the neck whiplash back from the blow, the body rags forward, crashing into the trunk, and there is nothing at all cartoonish about the injuries sustained. The villain’s breathing comes in gasps and fades gradually, gurglingly—the producer’s attention to this death stretching the limits of your willingness to watch, yet, by the same token, you’re still enthralled by the choreography of the design, by the perfect dance of the fight, which seems to you revolutionary for a cartoon.

#

You have passed into the time warp of watching. Your innocent Saturday has become a marathon. Your gaze adhered to the liquid crystal light filter. The frame of your laptop and the dim yet tangible room without is entirely dismissed while the story unfolds before you. Your mind has dialed down to the soft hum of synapse-activity, registering only the action and making the occasional necessary spike of effort to bridge plot gaps from episodes missed. But this requires little attention from your spongy brain; your computer is working harder in order to process the unrelenting stream you require of it.

Software and hardware both enjoy a lull while you squirrel leftover pizza from the fridge and munch and chase runaway crumbs (annoying nuggets of reality) and locate the next episode. The cooling fan whirs on again in anticipation. Enter again the theme song and montage, by now memorized practically pixel by pixel…

#

Episode 62: Graveland

By now, your heroine and her spring-loaded sidekick have left the peaceful towns of Trigsborough behind. The checkerboard fields and maple forests and wallpaper-white clouds are distant memories, and they are struggling shadow-accompanied through a hillocky land of scarecrows, stone Jotun-shapes in the distance. When they entered this territory, Loon had started counting the straw-skinned figures, but that was three episodes ago, and he gave up around a thousand, and they are denser now than ever before and more foreboding.

“I’ll bet a crow hasn’t been seen in these parts for ages.”

But Roco’s humor is thin, and she doesn’t respond, just continues her trudge. Overtime—that is, in today’s hours of binging—you’ve worked yourself into a lively crush upon curious Roco, her exaggerated anime figure alluring you into ever more intense staring, but it’s her features, which seem unique in the cartoon world, that bolster your infatuation. How sad and distant her mismatched eyes, how delicate her perfect peak of nose, how endearing her wild and impractical hair, which at present has fallen forward to shadow her face and amplify the tragic stature of her enchantment.

Even Loon senses her reflective mood as she pauses on the apex of a hill. Below them, as far as the eye can see, an endless mass of scarecrows shifts in the wind.

“They look like a vanquished army,” says the figure on Loon’s tie, English subtitles at the bottom of the screen scrolling on, off.

“They are.”

Loon’s cartoon surprise commits a new forecast to the sky. “What happened to them? Why are they scarecrows?”

“This was the last army that tried to turn Deadman back from the place where the Artifacts of the Black Rain fell. This is where they failed, and the First Jester turned them all to scarecrows so the families of the dead couldn’t come to bury their corpses.”

“Why would he do that?”

Roco doesn’t have an answer for the main villain’s motives. Says only, “He has to be stopped. Now more than ever.” And she sets off down the hill toward the ragged-coated strawmen, fishing rod flashing as though it were a hand retracting from a burn.

Though, or perhaps because, she speaks Japanese, Roco’s voice melts you with its emotion. It is the music. It is the way these animation’s eyes can be made to pulse with sadness that excites you to endure the endlessness of this saga’s serialization. There is always the mounting pathos. There is nothing less subtle, and yet you are in a frame of mind that lets you feel with Roco’s own sentiment the despair of seeing these dead and transmuted comrades again after so long.

As the plot unfurls (relinquishing secrets reluctantly as if the story was made from the outset to be endless), the episodes have become somber, the humor melting away to reveal the white bone and gristle at the story’s center. The lands they travel are more desecrated, the skies bedimmed by strange shadows. Bizarre hauntings accrue in the star-bright sky at night. Loon’s lust for Roco has matured into something you yourself long for with a cosplayer’s sense of hyper-participation. Your hand gropes for another pizza slice where there are none, and then slinks back to your lap, unnoticed.

In the world of the story—which is fast becoming the only world available to you—figures are advancing on the pair. It is clear from afar that they are Jesters. Two of them. One hulking, the other tiny and graceful, and as they approach, it’s not just the tiered logic of the henchman that tips you off as to which is the more dangerous.

The larger speaks first, while the other, a mime, hangs back, arms dead at her sides, hands hidden by bell-shaped sleeves that nearly drag on the ground.

“You’ve come far enough. This is Deadman’s land. Turn back.”

Roco considers the supercilious face of the hulk and decides to ignore him. She speaks to the mime. “I’ve seen you before. In the Kiakanjo Forest. You were with Deadman when he caused the original deathbed harvest.”

At her words, the episode folds origami-like into a flashback: a leafy, labyrinthine sequence that diverts the plot for two more episodes and takes you seemingly into the depthless pools of Roco’s memory. Here, too, she mentions the deathbed harvest to one of her comrades who later dies. It’s a reference to an event you’ve heard mentioned several times before. Something Deadman caused by collecting a set of artifacts that allowed him to raise the dead and make Court Jesters of them: a race of soulless, extravagant beings that have no number and seem only to grow more powerful the longer Roco and Loon travel.

When the elastic story is eventually allowed to snap back into the present, you’re left with more questions than answers, and you had almost forgotten about the mime and the hulk. Episode 70 ends as Roco and the hulk begin their fight, with the mime looking on.

#

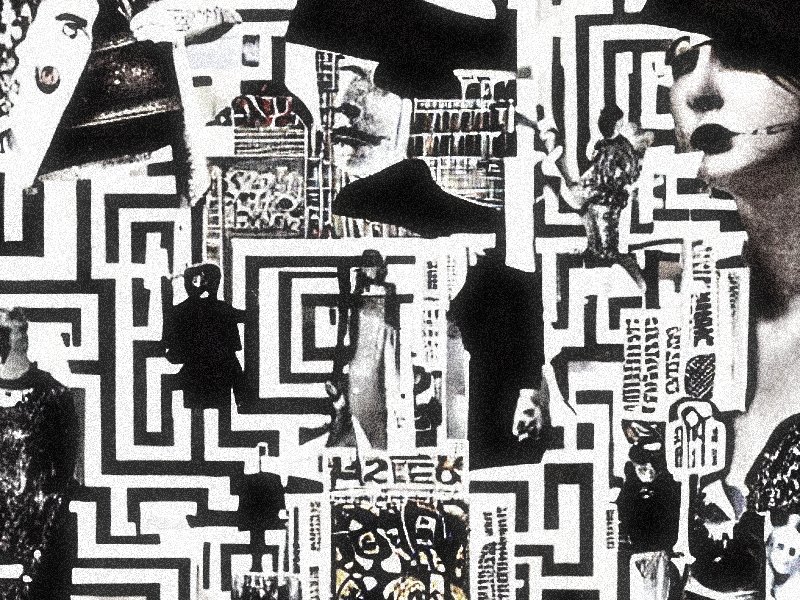

You feel as though your mind is conjuring this journey from nothing. A quick scan of available episodes takes you on a brain-numbing page scroll. Herein lies the remaining Saturdays of your life. You have entered an infinite unlinear maze—a digital concoction of what is really the only story that has ever been told: the one that doesn’t have an end. Rendered here, like life, literally.

And now that you think on it, neither had it any beginning. Without your notice, you’ve passed through a gate of Jester Race addicts, whose forums prove worshipful and collectively alarming. Alarming, that is, had you enough fresh air in your brain to be alarmed. Almost without your noticing, you’ve become one of those who are dependent upon the continuation of this story—one of a race of Jesters in your own right. Clients of the progression of the story, which always remains ahead of you. You have the sense of embarking on a vast peregrination without actually having left your chair. The power of the saga on the screen before your bleary eyes.

And maybe it’s not anything about this particular saga that keeps you here, well up into the night now, and barely taking care of yourself. It is the saga itself. The fact of serialization. The joy of sequential layering mirrored by the promise of eternity has crystalized into obsession. It’s life, it’s evolution, that captures you now. Not Roco or her endless fight—however dazzling—with Deadman and his Jester armies. It is instead the intangibility of any conclusion.

You know by now not to expect an actual end, and you don’t want one. When the creators grow too tired or too broke to continue with the narrative, the narrative will transition to the story’s true creators: the abounding and enigmatic viewers like you…

#

Episode 71: Jester Script Transfigured

The sequence in which Roco fights the mime is so spectacular it needs its own intro. The Jester Race has reached what might, in outdated television terms, be considered a new season. But literal seasons themselves are outdated, and anyway you’re insulated from all that outside nonsense by the temperature control in your room. You have everything you need, and there are layers of reality, some of which can be ignored.

Before you (there is no screen anymore, only the image, borderless), beautiful, eerie Roco stands on a pillar of a height with a close cratered moon amid the shuriken stars. She is alone. Loon has, episodes before, been revealed as one of the dreamdead: half-human, half-Jester—a man caught between life and death who seems a cartoon among cartoons. He has been demoted to the status of a spectator and might as well be sitting on the bed beside you, hunched forward to provide his jack-box head view of the elemental fight taking place.

The episode begins, and the mime lifts her sleeve-encased arms to reveal knife-soldered fingers. She advances with a series of cartwheels down the esplanade of awakening scarecrows. Yes, the scarecrows have been roused by this duel. Their shadows reflect the proud humans they once were, writhing in anticipation of the impending battle.

Roco begins to advance from her end. They are running toward each other now, trying to close a distance that has somehow grown during their inert standoff. Both of them producing dust storms in their wake, running at an impossibly blurred pace, closer and closer, until finally the scene freezes as if on a two-page manga spread: the mime and Roco glittering past each other, blade-thicketed. It is a last scrutiny of baroque detail, and then: the two are sliding past, turning on their feet in a meniscus of dust. Both appear unharmed. Have they missed each other?

But Roco’s mismatched eyes widen in belated alarm.

Your heart, unable any longer to produce changes of pace, doesn’t miss a beat as Roco drops to her knees in the mud. A trickle of blood runs from the side of her mouth. She curses in Japanese, and the snaking syllable seems in some way profound. Perhaps only in the context of all that has come before, which is compounded exponentially by flashbacks, intercessions of memory making the story anew. But the blood itself—the fight at large—has been reduced to hack-and-slash motion as though spliced together from individual drawings. Unshaded, at that. Two-dimensional, Roco stands to continue her crusade. Her wound is livid in some scenes, gone in others, and you realize what must be happening. The show is slowly voiding itself of visual elements. You were drawn, at first, by the flashy techniques, but by now the narrative has a life apart from the making of it, and you yourself are inextricable from its continuation.

#

The following episodes show you nothing beyond the theme song. Past that point is thirty minutes of black screen, which forum people claim they are still watching religiously—gazing benumbed at an empty space while the story plays out in some deeper abyss than their eyes. They argue plot points, compare collaborative character histories: Roco herself is a Jester who fought free of Deadman’s thrall. Roco is a human with certain Jester-like powers. Roco dies. Roco is reborn in a new, more powerful form. Loon returns as a Jotun Jester. Revelations abound. Histories collide and are rewritten.

It’s numbingly late now, and your body is calling from the distant planet you left it on, and it draws you slowly out of the dreamscape. Looking around your detail-less room causes you to perspire with a deep and joyless trance, and, though you’re fevered with exhaustion, you toss and turn and do not sleep.

But still you dream, your open eyes jittering as if in REM. You dream of The Jester Race. You run through a mountainous terrain of marble pillars and fallen, faceless idols. And the present is misconfigured, and the past interrupts whenever it likes and only as a means to distance from you further the drop zone future. There is only the sequence: the imperative that the story must go on and on and you a parasite on the back of its minstrel’s immortality.

In the sky, outside your window, the moon has become a grinning, toothsome face that leers below the constellation of a tri-belled foolscap…

Andrew is an author who lives in Grand Rapids, Michigan. His short fiction has appeared in journals such as The Collagist, Black Static, Into the Void, decomP, and others. His first book, Vessel, is forthcoming with Solum Press. Connect with him on Twitter @DrewReichard.